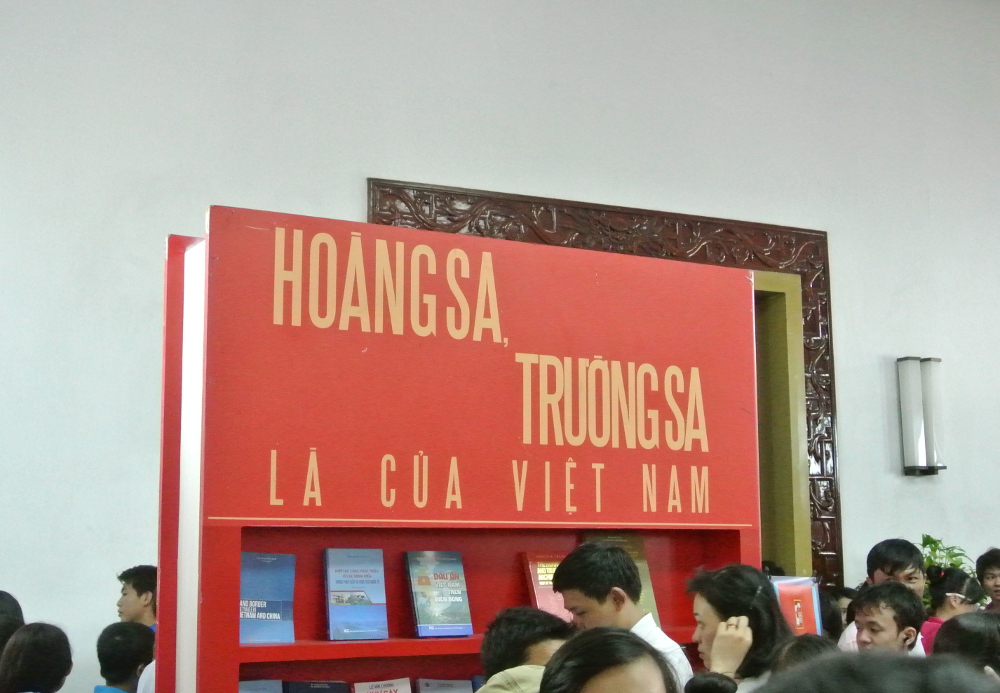

Vietnam claims Paracel and Spratly islands.

“An exhibition was officially opened for international partners and domestic citizens to observe the capacity, technological progress, and weapons and equipment manufactured by Vietnam.”

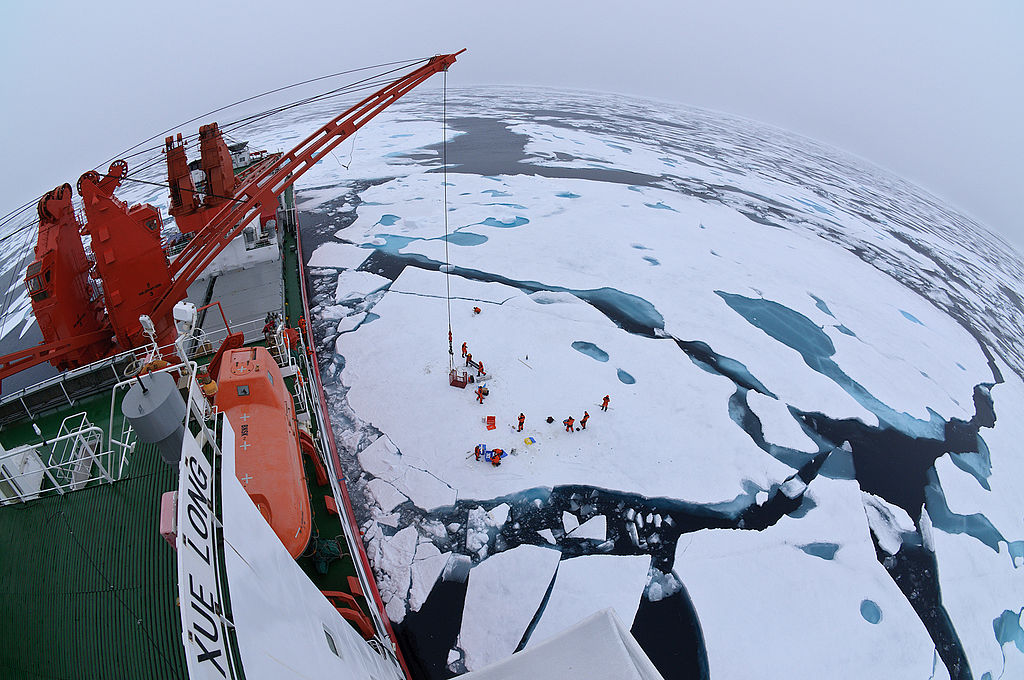

According to the first excerpted 6 April article from Vietnam’s national television broadcaster vov.com, the Vietnamese Ministry of Foreign Affairs deputy spokesperson denounced the National Natural Science Organization of China’s plans to conduct surveys in 33 areas of the South China Sea. Among the archipelagos in the South China Sea are the Spratly Islands (Truong Sa), which are claimed and controlled by Vietnam but are also claimed by China. Vietnam considers the Chinese survey’s encompassing of the Spratly Islands as an act of aggression. One way Vietnam has responded to China’s more aggressive military posture in the South China Sea, such as through surveying, is by branching out to multiple international actors to balance against China, if not also China’s ally, Russia. This was demonstrated at the 2022 International Defense Exhibition in Hanoi last December.[i] As the second excerpted article on the government-funded Voice of Vietnam website vtv.com noted, the exhibition was intended to highlight Vietnam’s military modernization and diversified international partners.[ii] While Russian artillery systems, which Vietnam has historically acquired for its army, were on display alongside Vietnamese ballistic missiles and unmanned aerial vehicles, there were also weapons from companies of Western countries and their partners, such as the United States, Czechia, Israel, and India. China was not among the nearly 70 countries that attended. The weapons at the exhibition are among those that Vietnam could acquire and employ during any future confrontation without relying on Chinese allies.[iii]

Sources:

“Việt Nam phản đối việc Trung Quốc công bố khu vực khảo sát bao trùm Trường Sa (Vietnam opposes China’s announcement of conducting a survey area throughout the Spratly Islands),” vov.vn (official website of the Voice of Vietnam radio broadcaster), 6 April 2023. https://vov.vn/chinh-tri/viet-nam-phan-doi-viec-trung-quoc-cong-bo-khu-vuc-khao-sat-bao-trum-truong-sa-post1012290.vov

Regarding the information that the National Natural Science Organization of China announced 33 survey areas, including some lines covering the Truong Sa archipelago in Vietnam’s waters, Deputy Spokesperson of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Pham Thu Hang at the press conference on April 6 stated, As it has repeatedly affirmed, Vietnam has a full legal basis and historical evidence to affirm its sovereignty over the Hoang Sa and Truong Sa archipelagoes based on international law.

“Người dân Hà Nội háo hức với Triển lãm quốc phòng quốc tế 2022 (Hanoians are enthusiastic about the 2022 International Defense Exhibition),” vtv.vn (Vietnamese government’s national television broadcaster), 8 December 2022. https://vtv.vn/xa-hoi/nguoi-dan-ha-noi-hao-huc-voi-trien-lam-quoc-phong-quoc-te-2022-20221208183916675.htm

On the morning of December 8, an exhibition was officially opened for international partners and domestic citizens to observe the capacity, technological progress, and weapons and equipment manufactured by Vietnam…. Many Vietnamese people witnessed the modern weapons of the army for the first time

Notes:

[i] Among the purposes of the exhibition was to “diversify defense equipment procurement sources” and to “introduce Vietnam’s defense capabilities and Vietnamese-made weapons” to the international community. Although Russia has historically been Vietnam’s main weapons supplier, the presence of Western countries at the exhibition indicates Vietnam’s interest in gradually diversifying by engaging in weapons transfers with them. See: “Vietnam hosts its first international defense expo.” rfa.org, 8 December 2022. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/vietnam/vietnam-defense-expo-12082022030531.html

[ii] Unlike Truong Sa, the Hoang Sa (Paracel Islands) have been under Chinese control since the Chinese navy expelled the South Vietnamese navy from the islands in 1974. The Socialist Republic of Vietnam has inherited the South Vietnamese claims over the islands since 1975, as well as concerns about China attempting to occupy Truong Sa in the future.

[iii] After 1991, Vietnam sought to “multilateralize and diversify” its foreign ties by normalizing its relations with China and all Southeast Asian states and becoming a member of Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC). By 2001, Vietnam and Russia revived bilateral relations in the form of a strategic partnership and Vietnam and the United States signed a Bilateral Trade Agreement. Vietnam’s broader goal was to insulate the country from Sino-U.S. competition or other major power rivalries and protect its independence and self-reliance. See Carlyle A. Thayer (2017), “Vietnam’s Foreign Policy in an Era of Rising Sino-US Competition and Increasing Domestic Political Influence,” Asian Security, 13:3, 183-199.

Image Information:

Image: Vietnam claims Paracel and Spratly islands.

Source: Tonbi Ko https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vietnam_claims_Paracel_and_Spratly_islands.JPG

Attribution: CC x 3.0